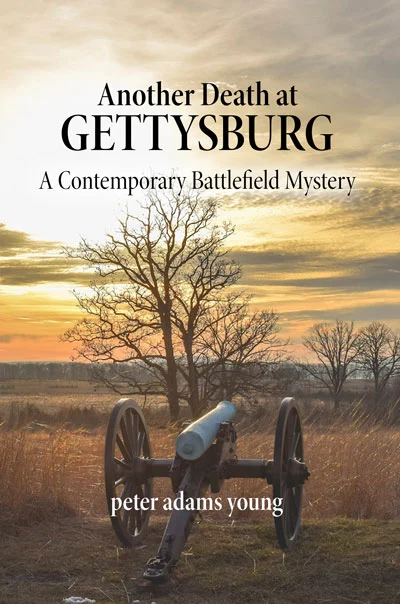

Another Death at Gettysburg

A Contemporary Battlefield Mystery

Book One of The Contemporary Battlefield Mysteries

JUNE 1997

An annual reenactment of Pickett's Charge ends tragically with the shooting death of a participant. When the investigation stalls, a Navy combat veteran and professor of American history is drawn into the challenge with his Vietnamese librarian wife — a journey that uncovers corruption, extortion, grand larceny, and ties to organized crime beneath the façade of local government.

In the follow-up to his award-winning debut novel of the Vietnam War, One Hundred Stingers, Peter Adams Young's Another Death at Gettysburg unfolds a modern-day murder mystery set in and around the historic Gettysburg battlefield.

Review by Military Writers Society of America

Peter Adams Young has done a masterful job with his new contemporary mystery tale, Another Death at Gettysburg. His characters are well-developed, likable (at least the good guys), and credible. The details of the story are vivid, and the language is colorful. At the annual reenactment of Pickett's Charge, our players are stunned to discover one of their own tragically shot with no reasonable explanation for the death. Is it an accident or murder? When the police investigators are stumped with several inconsistencies, a small group of reenactors take matters into their own hands. Newly relocated history professor Mike Davis and his librarian wife, Annie, are drawn into the camaraderie of the group. The mystery becomes more curious when it appears that several other crimes and motives are intertwined. But are they really connected, and how?

Young provides superb information about the role of the Civil War reenactors who keep our history alive—the men and women who are dedicated to authenticity and knowledge of the battles that shaped our country. Gettysburg was a victory for the Union and a turning point in the War, but many paid the price for that victory on both sides. The fields and hills of the battlefield belonged to farmers who not only had their land devastated afterward but also had to bury the dead (including horses), open their homes and barns to the wounded, and, over the years, unearth thousands of small and large artifacts.

Another Death at Gettysburg is a story well worth the read. Despite some minor technical errors, it is quick and enjoyable."

—Review by Sandi Cathcart (June 2024)